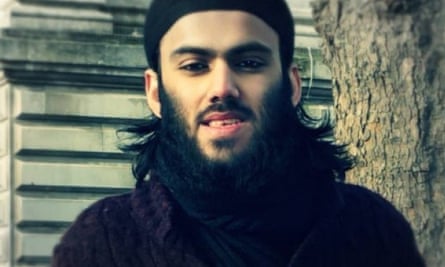

One British fighter, 23-year-old Ifthekar Jaman, who was killed in December 2013, coined the phrase “five-star jihad” to describe the fun he was having fighting in Syria. A number of “celebrity” fighters upped the ante. One of the most popular was a former Dutch soldier named Yilmaz, who helped train mujahideen fighters with various factions in Syria. He documented his Syrian experience with a wealth of photographs, posted on Instagram under the name “chechclear”, a reference to a gruesome video of Chechen insurgents beheading a Russian soldier in the 1990s.

As chechclear, he documented the war itself, posting pictures of battles and fighters, but also images of the people of Syria, including children, and seemingly incongruous snapshots of jihadists cuddling with cats, all of the photos enhanced by the photographic filters that helped make Instagram so popular. Yilmaz and other fighters also took to sites such as Ask.fm, a social media platform oriented around answering questions from other users. Questioners often asked how to donate to fighting groups or how they could get to Syria themselves, which fighters answered with greater or lesser amounts of specificity.

“I will personally assist you, inshallah,” Jaman told one questioner on Ask.fm. “But know this, if you are a spy, when you are caught, your punishment will be with little or no mercy.” Others asked what to expect if they joined, querying everything from food choices to bathroom facilities to what sort of gear they should pack. “Cargo pants (combat trousers), 511 brand is good,” wrote Abu Turab, a 25-year-old American who had drifted among fighting groups. “I have Old Navy, lol, but water-resistant stuff is the best. Don’t hesitate to buy expensive stuff , for you’re spending as [an act of worship]. Jackets and boots, try to buy Gore-Tex.”

The rise of violent infighting among jihadist factions in early 2013 and the subsequent disavowal of Isis by al-Qaida put a significant damper on the five-star jihad. But Isis was already moving to provide a new answer to the question: “Why join?” With the rollout of its plans for a caliphate in mid-2014, the focus shifted to promoting a sense of inclusion, belonging and purpose in its demented utopia.

The battle between Isis and al-Qaida is not simply between the organisations but between the visions they represent for the future of the jihadist movement. Al-Qaida represents the intellectual side. While its ideology runs counter to hundreds of years of Islamic scholarship, it is nevertheless carefully constructed and has been articulated over the years in considerable detail. Al-Qaida’s vision for the restoration of the Islamic caliphate is framed squarely in the long term. Its most frequently cited theme is a classic extremist trope – the defence of one’s own identity group against aggression. Its most charismatic leaders are dead. Those who remain are prone to deliver long hectoring speeches while sitting barely animate in a chair.

Despite its distorted worldview and its willingness to kill civilians, a-Qaida’s recruitment message is ultimately intended to appear “reasonable” and to resonate with a wide audience of thinking people. Of course, al-Qaida has seen more than its share of bottom feeders over the years. Terrorist groups naturally attract a certain number of thugs and violence junkies. But there is now a more natural home for members of that demographic – the Islamic State.

In July 2014, Isis’s al-Hayat Media Center released an 11-minute video that drove this point home. Titled The Chosen Few of Different Lands, the video showed a Canadian fighter named Andre Poulin, a white convert known to his comrades as Abu Muslim. It was a masterpiece of extremist propaganda. The video opened with stunning high-definition stock footage of Canada (or a reasonable facsimile) as Poulin described his life back home. “I was like your everyday regular Canadian before Islam,” he said. “I had money, I had family. I had good friends.”

The barbaric nature of Isis can lead observers to conclude its adherents are simplistic, violent and stupid. The Chosen Few displayed a keen self-awareness of this perception and actively argued against it, with Poulin as its telegenic exemplar. “It wasn’t like I was some social outcast,” Poulin said. “It wasn’t like I was some anarchist, or somebody who just wants to destroy the world and kill everybody. No, I was a very good person, and you know, mujahideen are regular people too . we have lives, just like any other soldier in any other army.” Life had been good in Canada, Poulin said, but he realised he could not live in an infidel state, paying taxes that were used “to wage war on Islam”.

In reality, Poulin was not quite the model of social integration that he portrayed on film. He developed an interest in explosives early and had dabbled in communism and anarchism before settling on radical Islam as an outlet for his interests. He had been arrested at least twice for threatening violence against a man whose wife he was sleeping with. These facts were conveniently omitted from his hagiography.

In the video, Poulin said Isis needed more than just fighters. “We need engineers, we need doctors, we need professionals,” he said. “We need volunteers, we need fund raisers.” They needed people who could build houses and work with technology. “There is a role for everybody.”

A narrator gave a brief account of Poulin’s life, with pictures, which concluded with an action sequence showing him taking part in an attack on a Syrian military air base in Minnigh. The footage was remarkable, depicting Poulin rushing toward the enemy, highlighted among his fellow combatants using sophisticated digital techniques. Poulin was clearly visible in action, running out in front of his comrades until he was struck down in a massive explosion. Afterwards, his dead body was shown sprawled on the ground and later being prepared for burial.

“He answered the call of his Lord and surrendered his soul without hesitation, leaving the world behind him,” said a narrator in perfect, unaccented English. “Not out of despair and hopelessness, but rather with certainty of Allah’s promise.”

At the end, Poulin spoke again, his visage filtered in a gauzy light. “Put Allah before everything,” he said.

The “whole society” pitch had been presaged for some months. Isis supporters on social media tweeted manipulated images of an “Islamic State” passport, for instance. But as Isis cemented its control of territory in Iraq and Syria, such images took on an increasingly material reality, albeit presented through carefully filtered glimpses. Each of Isis’s provinces issued a steady stream of images showing the infrastructure of government taking form – police cars and uniforms emblazoned with the black flag, markets overflowing with food.

While some of its outreach involved active image management, some parts were pragmatic, such as its offer of handsome salaries for engineers able to maintain the oil fields on which Isis relies for black-market income. In November 2014, Isis announced it would mint its own currency in keeping with the “prophetic method”, posting images of the new coins to Twitter. All of this also provided important markers of stability and substance. The stark black flag, which had come to be emblematic of Isis’s fighting force, was not just a symbol of war, the images argued wordlessly. It was the symbol of a society; no distant dream, but a living, breathing institution waiting to be populated by the believers.

With its heady media mix of graphic violence and utopian idylls, Isis has sought recruits and supporters who are further down the path toward ideological radicalisation or more inclined by personal disposition toward violence. Once these pre-radicalised fighters and their families arrive in Iraq and Syria, along with the foreign women recruited via social media as jihadi brides, they are exposed to an environment seething with traumatic stress, sexual violence, slavery, genocide and death and dismemberment as public spectacles. Among returning foreign fighters of previous generations, perhaps one in nine would eventually take up terrorism on returning to their homelands. The fighters of Isis are a new and untested breed. If they and their families one day attempt to return to their home countries, they will be unimaginably different from their predecessors.

Extracted from ISIS: The State of Terror by Jessica Stern and JM Berger, published by HarperCollins on 12 March