For the treaties marking the official end of the Cambodian–Vietnamese War, see 1991 Paris Peace Agreements.

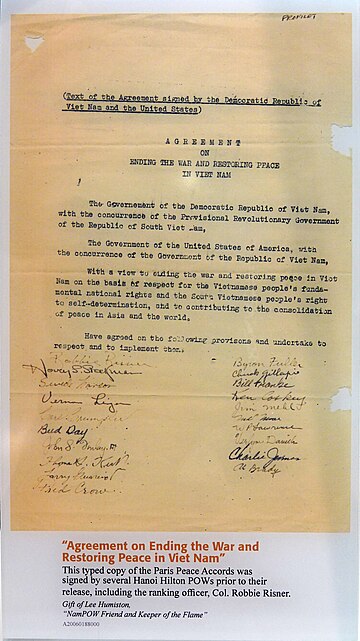

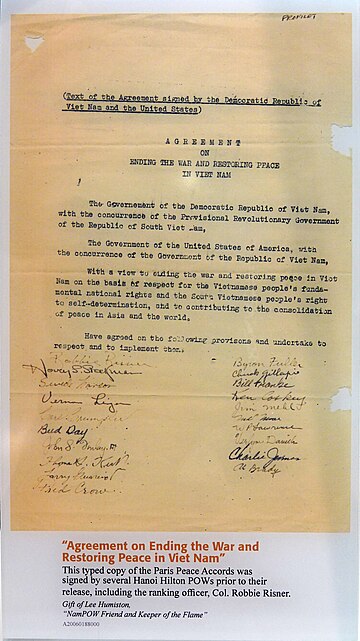

The Paris Peace Accords (Vietnamese : Hiệp định Paris về Việt Nam), officially the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam ( Hiệp định về chấm dứt chiến tranh, lập lại hòa bình ở Việt Nam ), was a peace agreement signed on January 27, 1973, to establish peace in Vietnam and end the Vietnam War. The agreement was signed by the governments of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam); the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam); the United States; and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG), which represented South Vietnamese communists. [1] US ground forces had begun to withdraw from Vietnam in 1969, and had suffered from deteriorating morale during the withdrawal. By the beginning of 1972 those that remained had very little involvement in combat. The last American infantry battalions withdrew in August 1972. [2] Most air and naval forces, and most advisers, also were gone from South Vietnam by that time, though air and naval forces not based in South Vietnam were still playing a large role in the war. The Paris Agreement removed the remaining US forces. Direct U.S. military intervention was ended, and fighting between the three remaining powers temporarily stopped for less than a day. The agreement was not ratified by the U.S. Senate. [3] [4]

Quick Facts Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam, Signed . Vietnam Peace AgreementThe negotiations that led to the accord began in 1968, after various lengthy delays. As a result of the accord, the International Control Commission (ICC) was replaced by the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), which consisted of Canada, Poland, Hungary, and Indonesia, to monitor the agreement. [5] The main negotiators of the agreement were U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and the North Vietnamese Politburo member Lê Đức Thọ. Both men were awarded the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts, but Lê Đức Thọ refused to accept it.

The agreement's provisions were immediately and frequently broken by both North and South Vietnamese forces with no official response from the United States. Open fighting broke out in March 1973, and North Vietnamese offensives enlarged their territory by the end of the year. Two years later, a massive North Vietnamese offensive conquered South Vietnam on April 30, 1975, and the two countries, which had been separated since 1954, united once more on July 2, 1976, as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. [1]

Part of the negotiations took place in the former residence of the French painter Fernand Léger; it was bequeathed to the French Communist Party. The street of the house was named after Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, who had commanded French forces in Vietnam after the Second World War. [6]

The agreement called for:

When Thiệu, who had not even been informed of the secret negotiations, was presented with the draft of the new agreement, he was furious with Kissinger and Nixon (who were perfectly aware of South Vietnam's negotiating position) and refused to accept it without significant changes. He then made several public radio addresses, claiming that the proposed agreement was worse than it actually was. Hanoi was flabbergasted, believing that it had been duped into a propaganda ploy by Kissinger. On October 26, Radio Hanoi broadcast key details of the draft agreement.

However, as U.S. casualties had mounted throughout the conflict since 1965, American domestic support for the war had deteriorated, and by late 1972 there was major pressure on the Nixon administration to withdraw from the war. Consequently, the U.S. brought great diplomatic pressure upon their South Vietnamese ally to sign the agreement even if the concessions Thiệu wanted could not be achieved. Nixon pledged to provide continued substantial aid to South Vietnam and given his recent landslide victory in the presidential election, it seemed possible that he would be able to follow through on that pledge. To demonstrate his seriousness to Thiệu, Nixon ordered the heavy Operation Linebacker II bombings of North Vietnam in December 1972. Nixon also attempted to bolster South Vietnam's military forces by ordering that large quantities of U.S. military material and equipment be given to South Vietnam from May to December 1972 under Operations Enhance and Enhance Plus. [20] These operations were also designed to keep North Vietnam at the negotiating table and to prevent them from abandoning negotiations and seeking total victory. When the North Vietnamese government agreed to resume "technical" discussions with the United States, Nixon ordered a halt to bombings north of the 20th parallel on December 30. With the U.S. committed to disengagement (and after threats from Nixon that South Vietnam would be abandoned if he did not agree), [21] Thiệu had little choice but to accede.

On January 15, 1973, Nixon announced a suspension of offensive actions against North Vietnam. Kissinger and Thọ met again on January 23 and signed off on an agreement that was basically identical to the draft of three months earlier. The agreement was signed by the leaders of the official delegations on January 27, 1973, at the Hotel Majestic in Paris.

This section needs additional citations for verification. ( August 2018 ) More information South Vietnamese armed forces, Communist armed forces .| South Vietnamese armed forces | |

|---|---|

| Ground combat regulars | 210,000 |

| Regional and Popular Force militias | 510,000 |

| Service troops | 200,000 |

| Total | 920,000 |

| Communist armed forces | |

| North Vietnamese ground troops in South Vietnam | 123,000 |

| Viet Cong ground troops | 25,000 |

| Service troops | 71,000 |

| Total | 219,000 |

The Paris Peace Accords effectively removed the U.S. from the conflict in Vietnam. Prisoners from both sides were exchanged, with American ones primarily released during Operation Homecoming. Around 31,961 North Vietnamese/VC prisoners (26,880 military, 5,081 civilians) were released in return for 5,942 South Vietnamese prisoners. [23] However, the agreement's provisions were routinely flouted by both the North Vietnamese and the South Vietnamese government, eliciting no response from the United States, and ultimately resulting in the communists enlarging the area under their control by the end of 1973. North Vietnamese military forces gradually built up their military infrastructure in the areas they controlled and two years later were in a position to launch the successful offensive that ended South Vietnam's status as an independent country. Fighting began almost immediately after the agreement was signed, due to a series of mutual retaliations, and by March 1973, full-fledged war had resumed. [24]

Nixon had secretly promised Thiệu that he would use airpower to support the South Vietnamese government should it be necessary. During his confirmation hearings in June 1973, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger was sharply criticized by some senators after he stated that he would recommend resumption of U.S. bombing in North Vietnam if North Vietnam launched a major offensive against South Vietnam, but by August 15, 1973, 95% of American troops and their allies had left Vietnam (both North and South) as well as Cambodia and Laos under the Case-Church Amendment. The amendment, which was approved by the U.S. Congress in June 1973, prohibited further U.S. military activity in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia unless the president secured Congressional approval in advance. However, during this time, Nixon was being driven from office due to the Watergate scandal, which led to his resignation in 1974. When the North Vietnamese began their final offensive early in 1975, the U.S. Congress refused to appropriate increased military assistance for South Vietnam, citing strong opposition to the war by Americans and the loss of American equipment to the North by retreating Southern forces. Thiệu subsequently resigned, accusing the U.S. of betrayal in a TV and radio address:

At the time of the peace agreement the United States agreed to only replace equipment on a one-by-one basis. But the United States did not keep its word. Is an American's word reliable these days? The United States did not keep its promise to help us fight for freedom and it was in the same fight that the United States lost 50,000 of its young men. [25]

Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese army on April 30, 1975. Schlesinger had announced early in the morning of April 29 the beginning of Operation Frequent Wind, which entailed the evacuation of the last U.S. diplomatic, military and civilian personnel from Saigon via helicopter, which was completed in the early morning hours of April 30. Not only did North Vietnam conquer South Vietnam, but the communists were also victorious in Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh on April 17, as were the Pathet Lao in Laos successful in capturing Vientiane on December 2. Like Saigon, U.S. civilian and military personnel were evacuated from Phnom Penh, U.S. diplomatic presence in Vientiane was significantly downgraded, and the number of remaining U.S. personnel was severely reduced.

According to Finnish historian Jussi Hanhimäki, due to triangular diplomacy which isolated it, South Vietnam was "pressurized into accepting an agreement that virtually ensured its collapse". [26] During negotiations, Kissinger stated that the United States would not intervene militarily 18 months after an agreement, but that it might intervene before that. In Vietnam War historiography, this has been termed the "decent interval". [27]

Portal: